Ashlen Renner

Ashlen Renner is an MFA candidate at George Mason University studying creative nonfiction. A former journalist and videographer from North Carolina, Renner is a 2022 travel fellow for the Cheuse Center for International Writers and has been recognized by the Hearst Journalism Awards for multimedia storytelling.

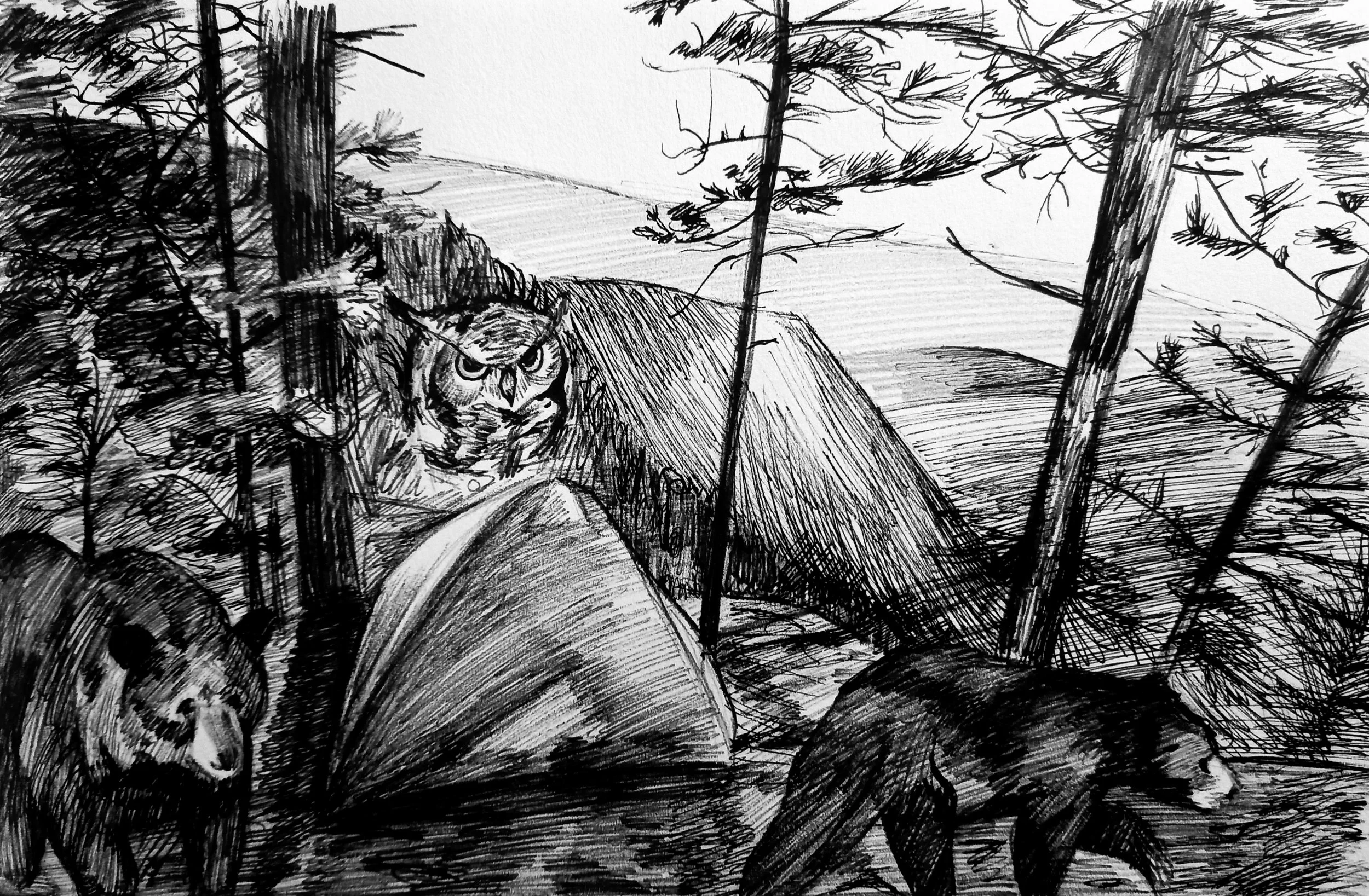

Bears of Shenandoah

Before the sun rose on my 21st birthday, an owl swooped down at my apartment window and screeched, piercing a hole in my dream like a jabbing finger to my gut. I jolted in my blankets. The owl hooted again. Even though the blinds were closed, I could imagine its unblinking yellow eyes staring at me as I fell back into the dream. The eyes followed me — a man with blank, glazed eyes peering into my tent through the mosquito netting, clawed feet raking the leaves outside, a bear’s sharp-toothed snout sniffing my hair. My body twisted into itself until I was curled inside a spiral shell of sheets.

The next day, I packed my car with everything I thought I would need for the week ahead — a camping pack with a 6 x 4 foot blue tent with a fleece sleeping bag, workout and “civilian clothes” rolled into crumpled cylinders in a small backpack, three pairs of shoes (sandals, flip flops, and hiking boots), $30 in cash, and enough food to last me for a few days if I rationed one peanut butter sandwich on white bread a day with an apple or an orange twice a day for snacks. I crammed everything in the trunk of my avocado green VW Beetle with the exception of my school backpack with the books I wanted to bring with me “into the wild”: Robyn Davison’s Tracks, Asexuality and Sexual Normativity: An Anthology, and The Poems of Robert Frost. I strapped that backpack into the passenger seat beside me.

Only my two roommates and a stranger from an asexual chatroom knew about my plan: a road trip crossing the North Carolinian Sandhills to the Appalachian Mountains where I planned to embark on my first overnight solo camping adventure. It was something I had always dreamed of doing—traveling free on the open road, cutting ties and restoring others, figuring out the route on the way—but underneath the upper crust of autonomy, there was a pervasive fear that I could not yet place. I remembered the dream that made my insides clench. Staring into the owl’s wide yellow eyes, I stepped into the forest alone.

A year before the road trip, I watched hummingbirds zip around my Great Aunt Louise’s bird feeder through the open screen door, overlooking the blank face of a mountain that used to be a ski resort. Grandfather Mountain loomed on the other side. It was a mountain most known for its face-like shape, like an old man lying on the ground with his eyes and nose scrunched in the direct sunlight. I had always been fascinated by it whenever I visited my Great Aunt and Uncle who lived in the mountain’s shadow. As a child, I imagined climbing on Grandfather Mountain’s broken nose, and feeling the earth sway under me as if the mountain were an ancient giant sleeping under a duvet of pine trees.

Aunt Louise shuffled to the couch and placed two sweating glasses of sweet tea on the worn wood coffee table as Great Uncle Bob watched baseball on mute from his armchair. Now that I was an adult, I was excited to be able to climb the mountain for the first time, but not before my elderly company instructed me on the dangers of the bear population in the Appalachian Mountains. If I encountered a black bear, I was supposed to stand up straight with my arms extended as far as they could reach over my head and shout at the top of my lungs, maybe stomp in place for extra flourish. If I saw a grizzly bear, I was supposed to play dead.

“It’s a predatory thing,” Uncle Bob said in his deep Southern accent. I assured him I would be fine on the trail. I had a bright orange whistle looped to my backpack, and I knew how to blow the Morse Code signal for SOS. I chose not to tell him that I didn’t know the difference between a grizzly bear and a black bear because the only bears I had ever seen were the wilted polar bears in the zoo.

“Well…ah…well good,” he said, taking off his thick glasses and wiping them on his shirt, breaking eye contact. Then I knew what this conversation was really about.

“Just be sure to be aware of four-legged animals, and as well as two-legged ones.”

“Hi, I’m Stuart. How are you?”

I sat cross-legged on my bed with my finger petrified over the mousepad. My first instinct was to log out, change all of my passwords, and shut down my computer, but then I remembered it was highly unlikely that this guy could be a pervert on a social media site for asexuals. I knew I should have waited a few minutes before responding, not wanting to look desperate, but fuck it — this guy was the first person to come out and admit his existence to me. I typed “Hello” back.

In a footnote of his book Understanding Asexuality, Anthony Bogaert recalled how he had once seen two crocodiles in love. They preferred to live in the same cage and slept on top of each other in the heat. No other animals at the crocodile farm in Northern Territory Australia showed the same affinity for one another.

“It made me wonder, a bit tongue in cheek, whether human love is partly a function of being in captivity,” he wrote.

I used to think of being alone like I imagine one thinks of a lover — imagining a life, years from now, in a small house on top of a hill, overlooking miles of rolling grassland or mountains or ocean or lake. Every place I dreamed was open, allowing me to stretch my arms as far as they could go and not touch anything but the crisp country air. In every place, I was alone. My roommate, Jen, once said I don’t need people to live, and maybe I went to Grandfather Mountain after my 21st birthday to prove her right or wrong. Out there, there was no mask, no cage, only soft earth and sweat.

I had never camped before, but I thought it would be similar to the solo hiking day trips I had taken in the Sandhills— this time with a bigger pack. My pack was stretched to capacity and dug into my shoulders. The thin straps were already fraying. The library copy of Davidson’s Tracks pressed against my back, a hardcover corner lodging itself under my shoulder blade while I clambered over roots and waist-high boulders. Now I knew how the author’s camels felt when they lugged her supplies across the Australian desert. After zigzagging up the trail, I made it to Grandfather’s balding forehead where the trees wore thin and rocks jutted out from the mountain into empty space. As I eased my way out, a middle-aged couple going down the mountain passed me.

“Staying the night?” the man asked. His skin was leathery and pulled tight around his bony legs, revealing impressive calf muscles.

“Yeah, that’s the plan,” I said, smiling through the exhaustion in my voice.

“Are you meeting someone up there?”

For a moment I thought of lying and telling him I was meeting a friend — a male friend — at McRae’s Peak, the mountain’s highest point. Most of the people who have ever questioned my solo treks on Grandfather Mountain were men. Their reactions to the truth ranged from half-hearted encouragement to overbearing concern. One year, a man even offered to escort me to my car halfway down the mountain. I declined, of course, telling him I would only slow him down. Though these men seemed to think I would be safer in the wild with a man, they were the reason I carried a can of pepper spray clipped to my pack, always in reach of my right hand.

“No, it’s just me,” I said, words tumbling out at the last minute. Maybe I told the truth because the man’s wife was there, or maybe I was tired of selling myself short, but the man’s eyes narrowed. His wife stood silent until she weaved around him and continued walking on the trail.

“Well, there’s a shelter back there if you get into trouble,” he said over his shoulder as he followed his wife.

“Thanks! Have a good hike!” I said in a retail voice as I continued my trek over the rocks. My smile fell.

Upon first virtually meeting Stuart on the chatroom, I started compiling little facts I learned about him since his first message, mostly scanning for red flags that would tag him as a perv. Stuart lived in Maryland, ten minutes away from the hospital where I was born. He worked in a physics lab. He hated traffic, and Maryland was flat and boring, but the job was good — as long as he didn’t have to write computer code too much. He liked cycling and hiking, though it took him longer than most to hike because he often stopped to take pictures. Nature photography, he said, is the hobby he took most seriously, but most of his pictures would end up in storage, gathering digital dust in hard drives. Shenandoah National Park was his favorite spot for photos, and though he loved the mountains, he didn’t particularly like hiking alone. I imagined what it would be like going on a hike with Stuart; we would probably march up mountains in silence, stopping every few paces to take pictures of flowers. I had always hiked alone, and I wondered if I would be able to enjoy the mountain’s solitude in another person’s presence, or if I would feel the need to fill the silence with chatter.

Stuart loved to watch animated Disney movies because he is sex-repulsed and couldn’t bear to watch anything else. It was one of the reasons he didn’t have cable anymore. He asked me what I was, and I said I was still figuring that out, but I felt like I fell somewhere on the asexual spectrum. Like birds, we flew in circles around this fact for weeks without actually touching it, but eventually we had to land.

“I kinda feel aces have transcended to some higher desire in life that most of the world doesn't get,” he wrote.

Stuart was not much older than me and had come to terms with his sexuality about the same time I did, but I subtly prodded to see if he had insight that I was missing.

“What would that be?” I replied. The text bubble hovered on the screen for an agonizing two minutes.

“Not sure.”

Heaving my pack higher up on my aching shoulders, I braced my foot on a boulder, attempting to stair-step my way up a rock wall, but it slipped down. My pack was too heavy, and my legs too shaky to climb. I peeled my pack off my shoulders, and just after I swung it on the landing over my head, I heard something cascade off the rock. One of my two-liter water bottles fell through a crack into a black abyss. When I peered in on my hands and knees, a chill wafted from the darkness so cold I could see my breath. I stood up, knees shaking like loose hinges. I had four more liters of water left, but the thought of falling so easily through the cracks made me gather my pack and turn around for another campsite.

I pitched my tiny blue tent on a platform under a cluster of cedar trees. I bought the tent for less than $20 at Walmart, and it was advertised as a children’s tent, but I figured if two five-year-olds could fit inside, I could squeeze in. I danced on my toes around the flattened rectangle of fabric, connected the flimsy plastic rods that were supposedly going to hold everything together, and fed them through the seams, careful not to tear through the fabric. The most difficult part was pushing the rods toward the center, which lifted the tent into its dome structure. No one else was there to hold the opposite ends into place. The dome deflated a couple of times before I forced it into its shape, splayed out on the platform like a wrestler. I stepped back to admire my work. This tent was supposed to shield me from the wilderness, but I couldn’t help but think of a bear plowing into the tiny, blue tent while I slept inside. A bear would crush me in a second.

By the time I finished, the light had turned soft, and all the day-hikers began to file back down the mountain. I sat hunched in the tent, listening to the last echoes of laughter fade until I was sure I was the last human left on the peak. I thought I would be empowered by this feeling, but as I watched the light dim, I began to realize I had trapped myself there.

I ran from my camp to an opening in the brush with a view of the valley and the mountain that used to be a ski resort. The cars on the road below glistened in the twilight, and every once in a while, the echo of a growling motorcycle or a speeding truck cut through the valley. I could see the life I could have. I drive to the grocery store with the windows down but the seat warmer on. I smile at strangers who pass me on the sidewalk, and sometimes make small talk about the weather. I go back to a cozy apartment with my roommates or home with my parents where I go to my room and close the door and listen to their footsteps padding lightly on the hardwood floors and their laughter blasting through the thin plaster walls. This was all I had ever known and never knew I would miss. Watching the sky turn pink and the mountains fade to blue, I recognized the complexity of what I wanted. I wanted the closeness of knowing other people, but I wanted the distance, too. I wanted to be able to have my own world in which I didn’t have to please anyone but myself. As soon as another person entered my life, the smiling mask came with it — the fake laughs, holding my breath before speaking, letting my voice die as another springs out. I was not afraid of people or relationships or commitment or love; I was afraid of the cage.

Before I could think about what I was doing, I typed, “I would love to meet you sometime.”

I was lying on my stomach in my tiny blue tent in the living room of my apartment. It was a few weeks before embarking on the trip to Grandfather Mountain, and I needed to practice pitching the tent. Plus, the Wi-Fi signal was good in there.

“Yeah, definitely. We should plan something. Not sure what or where,” he responded surprisingly fast.

“I was actually planning a trip to MD this summer to meet some of my old friends anyway,” I wrote, trying to sound nonchalant, but my fingers were shaking and I made so many spelling errors that I had to retype the entire sentence twice.

We agreed to meet in Maryland at the end of my trip. We planned to ride together to Shenandoah to hike Old Rag Mountain. The moment I pressed send on the message, it occurred to me that I was about to break every rule I was taught throughout my childhood. Don’t talk to strangers. Don’t meet up with a man on the internet. Don’t get in said man’s car. Don’t go with him alone.

I listened to the humming bees making one last trip to the mountain laurel flowers that grow in dense bushes along the rock. Then came the birds gathering and flitting from tree to tree, saying their goodnights. For a while, when the sky finally went dark, all was quiet except for the rhythmic whoosh of the wind drifting through the valley. I tried to project the image of the ocean on my eyelids, pretending I was sleeping soundly in the warm sand instead of shivering in the dark. Sometime after midnight, I poked my head out of the tent, still wrapped in my sleeping bag. Nothing stirred around me except for the leaves on the cedar tree. I looked up and saw the sharp, white stars through the cracks in the clouds. I had imagined seeing the stars, laying out on the rock and gazing up at the universe before me, but snot was frozen to my upper lip, and I was starting to shiver. I retreated back into the tiny blue tent, then curled in tight and shut my eyes, trying to relax the knot between my eyebrows.

At 3 a.m. the storm came. The peak of Grandfather Mountain is more than 6,000 feet up — high enough that his top half is often shrouded in a dense fog. I thought that being in a cloud would be pleasant, like sailing through a river made of cotton candy, but that was not the case. The inside of a cloud sounded like God trying to heave the mountain on its side in one breath. Even huddled under a blockade of trees, I could feel the wind spilling over the lip of the rocks and into my tent. I had seen how the trees bent back on the side of the mountain, and at that moment I understood why they stood permanently crooked. They were bracing for impact.

I had never felt so cold. When it came to supplies, I was dreadfully unprepared. It seemed impossible when I was packing my clothes in 90-degree heat that I would need a long pair of pants. I woke up every 30 minutes shivering, and my toes prickled inside my sweaty socks. I wrapped my raincoat around my bare legs and stuffed my socks with the nylon gym bag that I used to keep my food. I took off my bra, still damp with sweat, and layered my t-shirt shirt over my light jacket. I lay in a fetal position in my sleeping bag with the head hole closed so tight only my nose could fit through, counting the hours until sunrise, waiting for the warmth to come back, waiting for the wind to stop.

One hour before sunrise, something stepped on a twig outside the tent and froze. I imagined a bear with its paw poised just above the ground, staring at my tent. I stopped breathing. I had stuffed the food bag into my socks to save my toes, but now my food was scattered in the corner next to my head. The bear was going to maul me for stale white bread and a jar of peanut butter. Even though I heard nothing after a few moments, the image of the bear’s shiny quarter eyes and fang-tooth snout inching closer and closer to my head taunted me for hours. I cursed myself for being so stupid to think I would even be remotely prepared for this trip, for thinking I would be able to handle being alone, for not even telling my parents where I was going.

I needed the comfort of someone’s — anyone’s — company. I craved the warmth of another human body pressed against mine, something I rarely felt at all in everyday life. I remembered all the times my body stiffened when my best friend lay her head in my lap, how I used to brace my arm against my little brother’s boney chest as he tried latching onto me and cried for a hug, how I used to avoid sleepovers because I didn’t want to sleep in the same bed as anyone else, and how Jen always grabbed my wrist during the scary parts of movies because she knew I didn’t like to hold hands. Even though we had never met, I wished Stuart was there with me in the tiny blue tent.

A day before I was supposed to leave for the road trip, I offhandedly told Jen about Stuart. She was focused on studying for a Spanish exam and immediately forgot he existed. I figured it was easier that way, but it was a dangerous move. If he turned out to be a catfish, I was done for. I would get into his car and no one would even know where to look for me, but explaining why I was meeting him seemed more frightening.

Stuart and I had never met an open asexual person. We both had no idea how to explain ourselves. We moved through the world by passing as straight. We both sought validation that there were others like us, that the doctors were wrong to say that we had some sort of mental or hormonal disorder, that a man and woman can meet and just be friends.

The wind never stopped. At sunrise, the clouds sprinted past the mountain. The inside of the tent was damp with cold dew that dripped down the sides and coated the floor. I shimmied out of my elaborate sleeping position to take a piss. My knees were red and ached. I unzipped the tent and glanced in the direction of the bear. Nothing was there. The fog hung in the air, blurring the trees into the shapes of cocked elbows and knives in fists. I knew if I waited long enough the fog would lift, and I would be free of the cloud. I would have that perfect view of the mountains I had wanted for photos, but I didn’t care anymore. Every snapped twig and rustle of leaves made me bristle. I knew I had to eat, but I was not hungry, too cold to concentrate on anything for more than five minutes. Standing on the camping platform, I looked as far as I could into the woods and saw nothing, no one. It was a blank sheet of sky. I needed to get off the mountain. An hour after sunrise, I packed my tent, hoisted my pack on my now bruised shoulders without bothering to put my bra back on or to put my shirt back under my jacket. I zipped the raincoat around me and started back down the trail the way I had come. I was done with camping solo.

Back in the safety of my car, I messaged Stuart. I would not be camping in Shenandoah like I had planned. Of all the places I planned to go, Shenandoah was the one I feared most. Much of the park’s website was dedicated to how to store food so a bear could not get to it. I was supposed to hang my food bag from a rope in a tree 10 feet up and four feet from the tree trunk, but I didn’t own a rope long enough or a bear-proof canister. I also feared camping in the open wilderness. Grandfather Mountain was at least contained and flanked by roads and civilization, but at 200,000 acres, some parts of Shenandoah were more remote.

I had never been to Shenandoah, and the only inside knowledge of the park I had came from Stuart, who suggested I hike Old Rag, a nine-mile circuit on the eastern boundary of the park. Despite being the most difficult trail, Old Rag was the most popular trail in the park. Closer to the peak of the mountain, there is a rock scramble marked as strenuous and even dangerous by the park’s website. The website implied hikers should not attempt Old Rag alone, and after the incident on Grandfather Mountain, I was not going to test my luck again.

That night, I slept for four hours at a truck stop outside of Lexington, Virginia, feeling safer in my tiny, green car than I had in my tiny, blue tent. I knew I should have been wearier of the men in the sleeping hulls of trucks, but curled into the musty leather passenger seat, I was lulled to sleep by the sound of tires rolling down the highway. I pulled out at 4:00 in the morning toward Shenandoah. Driving on the empty backroads, I watched the dark ink blots of the Shenandoah Mountains drip into the watercolor orange sky, lines smooth as shoulder caps. It was a refreshing change from Grandfather Mountain’s crooked back and diaphanous shawl of fog.

I didn’t know why I came here if I was just going to come again within the next few days with Stuart. For a while, I entertained the idea of driving across the state completely to the coast where wild horses roamed the beaches of Assateague Island. I had no real attachment to Shenandoah, but it was a straight shot north of Grandfather, and the coast was another six hours away.

The sun rose on Shenandoah like a beacon on a lifeboat flashing against my eyelids. I had been sailing directionless on these mountains for days, but it was too late to turn back. I sat on the hood of my car and watched the beacon lift the shadows away from the old hills. I felt as if I had been on this journey forever, but at the same time, it was like a fresh start.

I started with Hawksbill Peak and worked my way down Skyline Drive to Lewis Falls, then Big Meadows. In my sleep-deprived state, I was often startled by the shapes and movement of bushes and trees, thinking that a pack of bears was stalking me. Every bear sighting made my body hiccup back to consciousness, only to realize that the bear cub I thought I saw scratching its back on a tree was actually a low-hanging branch bouncing under a squirrel’s weight, and the bear rustling in the bush was just a murder of crows scavenging for twigs.

The bear I saw on the trail between the falls and the meadow was real. He was about five feet of black, puffy fur, shoulders hunched down with a small cone head with a light brown snout. A gaggle of retiree tourists were watching him through expensive lenses, cameras clicking. A man with red-rimmed glasses was moving too fast, stepping on twigs while he inched toward the bear, trying to get a better shot. The bear was not cooperating. He cast his nose down in the ferns like a shy child, only lifting his head after lumbering behind the trees. The bear moved slowly as if he were sleepwalking, and did not seem interested in the group of humans on the trail. He waddled away apathetically. I almost laughed at how I had once been afraid of these animals, how I imagined them mauling me in my tiny blue tent. The truth is, I later learned, bears don’t usually bother humans; there have been only fifty fatal black bear attacks recorded since the 1880s. Trash-picking seemed to be the only trouble they caused.

I left the tourists to take their high-resolution photos of the bear’s behind, continuing on the trail until it opened up into grassland. There, I saw three more bears — a mother and two cubs — crossing the trail back into the woods. We both stopped and looked at each other. Her eyes were black and glassy, almost invisible in her dark fur. She was not afraid of me, and I stood paralyzed, not because I was afraid of her, but because I was in awe of this wild creature standing so poised and calm. She didn’t scurry away or launch up on her hind legs to mark her territory. After a moment, she dropped her head to one of her cubs stumbling across the path, and disappeared in the ferns, allowing me to exist in her world.

“I’m here,” I texted.

We met at 5:00 in the morning in a parking lot of a 24-hour Harris Teeter in some Maryland suburban town between Baltimore and Washington D.C. He pulled in beside my car, leaving one space between us, as I sat in the trunk of my Beetle pulling on my dirt-crusted wool socks. I tied my boots with shaking fingers, pretending to be preoccupied as I watched his every move from the edges of my vision and under my eyelashes. He could have been anyone — a serial killer who kidnaps virgins on the weekends. When he stepped out, standing tentatively in the space between our cars, I determined he was not who I feared.

Stuart was all dimples, a schoolboy overgrown with socks pulled high on his freckled legs, frizzy russet hair cut close to his head, and cloudy blue eyes with flecks of light brown. He could sunburn to the knuckles. I shoved the second boot on my foot and stood up. I had traveled more than 500 miles to get here, and I didn’t come all that way for awkward small talk.

“Can I hug you?” I asked after exchanging greetings and comments about the weather.

“Oh,” was all he said before he lifted his arms slightly from his sides.

I was not much of a hugger. I tended to extend my arms farther than the rest of my body, leaving a gap between me and the other. I had a slight aversion to people touching me, but I never refused a hug mainly out of politeness, rarely asking for them. As I stepped closer, I caught the fresh scent of his cologne and aftershave and wondered what I smelt like — probably week-old sweat and soggy leather and dry spray shampoo and truck stop bathrooms where I had scrubbed my face with a cheap bar of soap. I wrapped my arms around him anyway, and it felt easy. Books told me how women were supposed to melt in a man’s arms, which I never fully believed, but in that moment, a layer of me cracked open. The last of the crust formed after Grandfather Mountain chipped off of me, the shell of loneliness crinkling in his hands. We both let go before it became too much. He wasn’t a fan of the touching either.

While hiking Old Rag, I could never look him directly in the face. I didn’t want to trip (I did anyway — twice). We stopped to take pictures and sat cross-legged on the rocks comparing camera settings. We were easy friends, and our laughter cascaded off the mountain. I was afraid he wouldn’t laugh — that he would be stiff with a stern face. The word frigid came to mind, falling prey to a stereotype that people often assigned to our sexuality. I made it my goal to make him laugh. I accomplished that within the first two minutes of the hike. I forgot what I said, but it may have been the strange newness of all this that made the laughter froth from our mouths.

I stared a lot at his grey wool socks and the back of his browned hiking boots. I watched his feet on the scramble as he lumbered over rocks, not the most graceful, but he made it up nonetheless. I tried to copy, hitching my pack up and stretching my leg up the boulders, but my pack pulled me back, and I constantly felt like I was going to fall flat on my back off the mountain. Stuart saw me falling behind and stopped, stretching his arm toward me. His hand was large and swollen from the heat and scraping his palms on the rocks. It was warm when I took it, and though I didn’t anchor my entire weight on him, it was just enough so I could pull myself to steady ground.

Illustration by Annabelle Starr